Driverless vehicles will be a reality in our digital lives, and the car insurance industry of the future will need to meet the challenge of this radical change

Motor insurance stands on the cusp of momentous change. It is no exaggeration to say that by the end of the next decade it will be a fundamentally different industry from the one that has barely changed over recent generations.

The 1980s revolution in direct insurance and the more recent arrival of comparison websites may have reshaped the distribution model but they were merely different ways of selling the same product. Now, the product is changing because the vehicles themselves and the attitudes towards ownership are changing at an unprecedented pace.

The role of insurers will be transformed, says James Rakow, insurance partner at Deloitte. “Insurers will embrace the safety agenda through the advent of semi-autonomous vehicles by moving outside the pure underwriting role to a risk-management and risk-mitigation role. They will also have to develop a multi-modal way of looking after people’s insurance needs, because they will also need to focus on the carless driver as much as the driverless car.”

Impact of the sharing economy

Young adults learning to drive today are growing up in a world where car sharing is more commonplace and ride-hailing services are a regular form of transport. Many anticipate that young people will not own cars to anything like the same extent as their parents, because it is no longer an aspirational milestone in life.

Jonathan Dye, head of motor at Allianz UK Insurance (Commercial), said insurers are ready for this challenge. “We have to innovate to ensure society has the insurance it needs to support these changes. Insurance has always been an enabler. It has always been about enabling people to take risks so that society and commerce can progress.”

The response will vary around the world, says Mr Dye: “The culture of a country is important in how it embraces the sharing economy. In the UK, this is likely to see the emergence of mobility insurance in the form of short-term insurance taken out for specific journeys in different vehicles.”

Mr Rakow sees this as the most likely model too, with data at its heart. “What is going to be very important is the portability of people’s driving data. People will share their data if they can see the benefits, but they will want real clarity on what those benefits are.”

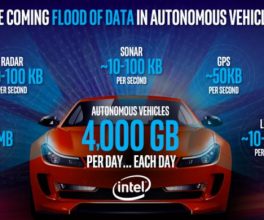

Collecting and using that data will be a two-way process, says Graeme Trudgill, executive director at the British Insurance Brokers’ Association (BIBA), especially because connected cars open up new opportunities for insurers to engage with policyholders, and vice versa.

“InsurTech means that there is a huge potential to engage more with drivers to help them understand how their driver behaviour can impact their insurance premiums,” he says.

New driver demographics

Martin Bridges, BIBA’s technical services manager, says insurers will also have to respond to changes at the other end of the demographic age scale as autonomous vehicles become more common, at least in certain driving environments. He says: “Autonomous vehicles have huge potential when it comes to older drivers, because it will allow them to retain their mobility.”

While insurers should embrace the emerging opportunities created by demographic change and vehicle automation, Mr Bridges stresses that they must not lose sight of the customer especially those living in rural areas where car ownership is almost obligatory to avoid social isolation, and where the driving environment is unlikely to lend itself readily to automated vehicles.

Pressure on costs

The biggest benefit consumers will expect is a reduction in the cost of insuring their mobility, especially as autonomous safety features and connectivity become the norm in new cars. However, Mr Dye cautions against expecting too much change too soon.

“We know that the evolution of ADAS [Advanced Driver Assistance Systems] and other safety features reduces accident frequency and improves safety. That can only be a good thing but it won’t immediately reduce claims costs. When cars with these systems crash they cost more to repair. But that [price] is only likely to be short-term as the cost of technology eventually comes down and the frequency of accidents reduce.”

He adds that there are other pressures pushing up repair costs: “The devaluation of the pound means that repair costs are going up because we have to import parts. We’re seeing double-digit inflation in the repair of bent metal.”

Repairs aren’t the only costs under pressure. Claims costs, for personal injury as well as for repair, are also increasing, says Stephen Jones, lead, UK P&C pricing practice at Willis Towers Watson. He cites the shock change to the discount rate (the so-called Ogden rate) for calculating personal injury claims settlements as a key contributor to this upward pressure. The change added millions to insurers’ claims bills and although further changes easing the rate and the costs to insurers have been promised by the Government, these will not be implemented before the end of 2019 at the earliest.

“We’ve seen this year – with Ogden and other influences – that motor insurance premiums might not reduce as fast as some people anticipated. As the tech goes into cars the repair costs go up and many vehicles now almost have a sensory overload. This means that the upward impact on claims costs has come through faster than the reduction in frequency.”

Autonomous cars: a double-edged sword

This potential for autonomous vehicles to be a game-changer when it comes to reducing accidents both excites and unsettles insurers.

The possibility of third-party accident claims almost disappearing has already prompted Forbes to warn the US insurance industry that premiums for conventional motor accident insurance might come down by as much as 75pc by the end of the next decade, sparking a wave of consolidation and realignment.

With more than 90pc of accidents caused by human error, such predictions need to be taken seriously. Automated emergency braking, lane-drift sensors and self-parking are already joining established safety features such as anti-lock braking in new cars, so the autonomous vehicle – with the potential to be driverless – moves ever closer. The rush to understand the implications of its imminent arrival is underway.

In the UK, Government and manufacturer investment has brought us to the crucial level 3 stage in the development of autonomous cars, where cars will be able to drive themselves but will hand back to the driver when facing situations they can’t handle (see box-out 1).

It is not just insurers that need to keep up with the pace of development – the legislators also have a challenge on their hands. New laws in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Bill will ensure clarity in how liability for accidents caused by automated vehicles should be apportioned (see box-out 2).

In Germany, the pace of change is even faster, as new laws have just been passed to allow fully autonomous level 5 cars on public roads. Scandinavian countries are also looking to get fully automated vehicles onto their roads by the end of the decade.

In some ways, insurers are more comfortable with fully autonomous vehicles than they are with the transitional phases, says Peter Allchorne, partner at DAC Beachcroft.

“Level 3 automation brings with it many risks and in many ways we would be better skipping this stage entirely. It highlights the absolute need for serious public awareness and education. When you are looking at these developmental phases that fall just short of driverless, there is a real danger that a driver could be lulled into thinking they are driverless when they should be taking control.”

These worries are shared by some major motor manufacturers. Jim McBride, Ford’s autonomous vehicles expert, said recently that Ford wants to move straight to level 4, since level 3, which involves transferring control from car to human, can often pose difficulties. “We’re not going to ask the driver to instantaneously intervene. That’s not a fair proposition,” McBride says.

Mr Dye says insurers also view the limitations of level 3 vehicles with concern: “People will disengage and they will not be ready to take back control in an emergency. With manufacturers also warning of these dangers, we believe we have to be ready for the challenge of insuring level 4 vehicles within three to four years.”

Driverless cars – phases of development

Level 0:

The human driver controls it all: steering, brakes, accelerator.

Level 1:

This driver-assistance level means that most functions are still controlled by the driver, but a specific function (such as steering or accelerating) can be done automatically by the car.

Level 2:

At this level, at least one driver assistance system is automated, such as cruise control, lane-drift sensors, front-rear braking or automated parking. It means that the driver is disengaged from physically operating one or more aspects of the vehicle, potentially at the same time. The driver must still always be ready to take full control of the vehicle.

Level 3:

Drivers are still necessary in level 3 cars, but are able to completely shift safety-critical functions to the vehicle under certain traffic or environmental conditions. It means that the driver will intervene if necessary – often prompted by the vehicle.

Level 4:

This is fully autonomous operation. Level 4 vehicles are designed to perform all safety-critical driving functions and monitor road conditions for an entire trip on suitably maintained roads. However, it does not cover every driving scenario and there will be situations when a human can opt to re-take control of the car.

Level 5:

This is the most sophisticated fully-autonomous mode where the vehicle’s performance is expected to equal or better that of a human driver in every driving scenario, including extreme off-road environments.

InsurTech will improve claims process

One area in which consumers should quickly see improvements is claims handling, says Mr Rakow, especially as dashcams and telematics become commonplace.

“Once there is more objective information around the circumstances of an accident, it will change the way liability issues and responsibility for accidents are determined. It also offers the potential to eliminate certain types of fraud.”

Telematics has been high on the list of developments that excite insurers, but its take-up has been limited so far, says Mr Jones. “Telematics has really only become popular with younger drivers who are struggling with affordability.”

One of the potentially attractive features of telematics to insurers, in addition to recording data that can be used to resolve claims, is the opportunities it opens to connect with policyholders more frequently, although Mr Jones cautioned against expecting too much from this.

“There are some big questions over whether customers will really find that more convenient. The insurers would certainly welcome the opportunity for more frequent engagement but I question whether that is really what customers want.”

The adoption of dashcams is likely to move faster than telematics, he says.

“It is already a significant rating variable. At the moment, we are seeing a high degree of self-selection by the more safety-conscious motorists, but they will soon be a standard feature in mid to high-end vehicles.”

Cyber risk in connected cars

Where there is greater connectivity, there is cyber-risk. Some manufacturers are making bold claims about how resilient their vehicles’ systems will be to hacking, but insurers are more realistic, says Mr Dye. “If you can control the car from your phone, then there is a greater probability for the car to be hacked.”

“There will have to be mechanisms and policies in place to pick up the hacking outcome. That could create a liability dispute between the motor insurers, vehicle manufacturers and software providers,” says Wendy Hopkins, partner and head of the global practice group at DAC Beachcroft.

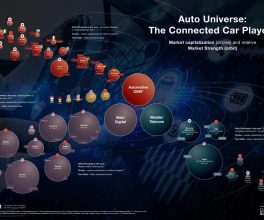

These new risks could draw new players into the market, says Mr Rakow. “The mobility eco-system is changing and as it does we will find adjacent players looking at the market. They will bring new ideas, new distribution methods and pose fresh challenges to the existing players”.

Many people have assumed the main interface when it comes to recovery will be between the frontline motor insurer and the insurers of the component manufacturers, installers and repairers, but this will only be part of the story, says Wendy Hopkins, partner and head of the global practice group at DAC Beachcroft.

“The interconnectivity and the ability of the vehicle to communicate effectively with the highway infrastructure is absolutely key,” she says.

There was a recent accident involving a Tesla driverless car which hit a brick wall because the white lines on the road had become obliterated. In another trial a driverless car stopped in the middle of the road because it came across a pothole and didn’t know what to do.

“These highlight the need for a major new investment in the highway infrastructure. The authorities have a maintenance obligation now but this is obviously a huge extension of that”, says Ms Hopkins.

Who pays the claim?

The Automated and Electric Vehicles Bill will require a Road Traffic Act-compliant insurance policy to be in force for every vehicle. The motor insurer will handle the claims regardless of the cause, even though in some cases the driver could effectively be a passenger if the vehicle is operating autonomously.

Insurers will pay the claim but then have the option of pursuing recovery from a product liability or professional indemnity insurer if one of the increasingly complex parts or systems failed or wasn’t installed properly. This won’t be automatic or easy.

The onus will be on an insurer to identify where they believe liability lies. This could be with component manufacturers but also software providers or highway authorities. It could also be a repairer if a previous repair and recalibration of safety systems was not carried out correctly.

Insurers will still have to show that the manufacturer or installer was negligent if they are to recover from them and they, in turn, will still have a state-of-the-art defence to rely on.

Brought to you by – Allianz

Courtesy of The Telegraph