When Jim Dykstra became part owner of his family’s auto repair service business in 1994, mechanics diagnosed car problems by looking under the hood. Soon after, car manufacturers started to add computer controls to vehicles’ steering wheels, airbags, brakes, windows, mirrors, and just about everything else. Dykstra’s current Audi has around 75 computer modules in it, and employees at his three repair shops near Grand Rapids, Michigan, are more appropriately called “technicians” than mechanics.

Technicians often start a repair not by poking around an engine, but by plugging a computer tool into what’s known as an “On-board diagnostics (OBD port”—a cracker-sized opening, often located under the dashboard, that looks similar to one you may have seen on a computer monitor or DVD player. They then read trouble codes from those tools’ screens. “P0306” means a cylinder 6 misfire. “P2706” means a shift solenoid F malfunction. Other trouble codes require specific software or access from different manufacturers to read and understand. There are tens of thousands of codes, and the way to fix the problems they diagnose might be different for every single make and model of car.

Fixing some problems in today’s new cars requires some relationship with their manufacturers. This has been the subject of a massive negotiation, similar to the debate over whether smartphone manufacturers like Apple should make it easier for other companies to fix their phones. With cars, though, the whole argument is about to change: because as much as computers have already changed cars, connecting those computers to the internet could change the auto industry even more.

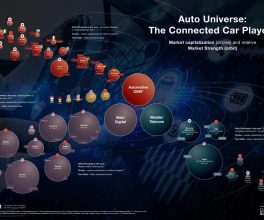

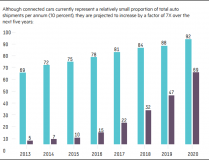

By 2020, Gartner predicts, 250 million connected cars will be on the road, about one in every five vehicles worldwide. Connected cars offer more than elaborate infotainment systems: They will also allow manufacturers to remotely monitor a vehicle’s health, predict what maintenance work and repair work it needs, and to diagnose its problems.

Car manufacturers have just begun to explore ways to expand business opportunities that could be built on connected vehicles and all of the data that come with them. GM’s Onstar, for instance, tells customers when they need an oil change or when their brake pads need to be switched. These recommendations are not based on the traditional “it’s been 3,000 miles” timeline, but upon sensors that monitor what is happening in the car and things like the climate of your area. Tesla says it can spot 90% of service repair issues remotely, so it can order parts and have them waiting for customers at its repair centers. But there’s more to be done.

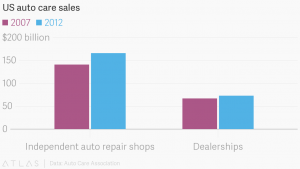

Some worry that eventually, services like GM’s Onstar could share data they receive from connected cars with local GM dealers, who offer repairs and maintenance service, but they won’t necessarily share this type of information with Dykstra or the other 180,000 independent auto repair businesses in the United States, which could leave them at a disadvantage. Or worse, manufacturers will move data that shops need to fix cars, some of which is currently accessible by the OBD port, to these new connected systems, where it will be less accessible to independent businesses.

“Dealerships will send you a message that says ‘your oil sensor says that your oil is ready’ and we have a bay open at this time, come on in,’” says Greg Potter, the executive manager of the Equipment and Tool Institute, a trade association of automotive tool and equipment manufacturers. “It’s a good idea, a good model. But very difficult to compete with.”

That would impact not only repair service businesses like Dykstra’s, but also the companies that sell these shops parts and tools, which together with repair shops that aren’t associated with a dealership are called the “aftermarket.”

If this sector, which sells around 70% of all auto care parts and services in the United States, mostly for vehicles that are no longer covered by warranty, doesn’t have adequate access to information streaming from cars, Dykstra says, “a whole $300 billion-plus industry—we’d be up a creek.”

Safety first

It took the automotive aftermarket and car manufacturers more than a decade to sort out how to share repair manuals, diagnostic codes, and service documents that allow technicians to fix today’s cars in the United States. In 2014, fearing a mess of state-by-state legislation after a “right to repair” law passed in Massachusetts, two automotive associations, which together represent nearly every car manufacturer, signed a memorandum of understanding agreeing to give equal information access to repair shops outside of their dealership networks.

But the memorandum didn’t address how data transmitted by a connected vehicle—the data that would allow shops to understand when a car needs maintenance before the customer calls— would be shared. And so many of the same automotive industry groups that worked on the agreement to share repair data have shifted to that problem.

The biggest concern is how to share data in a safe way. In 2015, Wired published an article that demonstrated how hackers could control a moving vehicle by exploiting its wireless connection capability. The hackers wrote a white paper about vulnerabilities in connected cars that inspired the FBI and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration to issue a public service announcement warning connected car customers to be “aware of potential threats” of hackers.

Two potential standards for securely sharing data from cars have emerged. Both would provide access to data for multiple approved users—if your repair shop and your insurance company both wanted different portions of your car’s data, and you agreed, they could both access it. Both propose security features that aim to protect private data (you probably don’t want your car technician to download your entire geolocation history, for instance).

The first solution places more control of data in the hands of a manufacturer. If a repair shop, a parts dealer, a tech school, or an insurance company wanted access to the data coming out of a car, they could license it from a manufacturer such as Ford, General Motors, or Toyota, or access it under some agreement.

BMW has already experimented with this type of system. Called “BMW CarData” it allows customers to share their cars’ data with third parties, such as insurance companies that want to keep tabs on their driving habits or an auto repair shop. But the data runs through BMW’s servers first.

The second solution, for which aftermarket trade organizations have advocated, could rely on independent registration authorities and the gateway could be located within an individual car rather than in the cloud of a manufacturer. Manufacturers would no longer necessarily be the brokers of that data.

Shops like Dykstra’s currently have a work-around option to accessing data like when a customer’s oil is due for a change. Their customers can plug a dongle into the OBD port, the same place where technicians plug their diagnostic tools, that will connect to the network to share data. Car parts supplier Delphi, for instance, introduced such a system in 2012. Verizon makes another. Dykstra founded and sold a company that makes interfaces for this data, allowing shops to proactively contact customers when it’s time for their cars to be maintained.

But the dongle only allows for one entity to access data: Customers can install a dongle from an insurance company or Delphi, but not both. It also has security flaws.

Legally, data about a car’s emissions must be made available through this port—it’s why the port was mandated in the first place. But much of the information that technicians read through the port that helps them fix cars doesn’t have to be there. It could, aftermarket industry advocates worry, be transmitted wirelessly to the car manufacturer, where the car manufacturer could control access to it.

A long conversation

Car manufacturers have taken different stances on how much data they should be expected to share with repair shops that aren’t part of their dealerships. Some say they want to cooperate with the aftermarket as much as possible. “Automakers can’t force every vehicle to get repaired by a dealership,” says Daniel Gage, a spokesperson for the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers, an automotive industry advocacy group that represents 12 major car manufacturers, including Ford, GM, and Toyota. “The math just doesn’t work out.” Others, like Tesla, have created barriers between its cars and independent repair shops, instead of servicing all vehicles directly.

Gage says that fears that car manufacturers will restrict access to data are unfounded. “[The memo of understanding] guarantees the aftermarket access to all OEM diagnostic tools, service information, and associated training resources that are provided to their independent franchised dealer partners and are needed for repair and service, regardless of how those tools and information are presented,” he says.

Not everyone is so sure. “The net of it is, we don’t know,” says Behzad Rassuli, a senior vice president at the Auto Care Association, a trade association that counts 500,000 independent manufacturers, distributors, parts stores, and repair shops as members. “We don’t know what data is going to be available from where. That uncertainty is enough to send us into action.”

Last December, a group of 10 auto industry organizations that represent both car manufacturers and aftermarket players wrote a letter to SAE International, a standards-setting agency, to create a working group around the type of information sharing system that aftermarket repair shops favour. This was not necessarily a concession.

The letter did not suggest that the groups agreed that this was the best system, and even if it had, there would still be no agreement on the details. Will aftermarket repair shops have access to the same data as dealerships? Will they have it at the same time? How much will they need to pay to access it, if at all?

Some industry experts aren’t optimistic that whatever agreement, or lack of agreement, manufacturers reach with the aftermarket will put repair shops on equal footing with car dealerships.

“[Car manufacturers] are investing billions into this and they really see this as core intellectual property,” says Gianluca Campione, a senior partner at McKinsey who coauthored a 2016 report on monetizing car data. “Independent workshops will very likely have a role, but if you look at the types of repair they do today, it’s often simple maintenance, routine inspections. Those mechanic shops would know how to fix a steering system, but if that steering system is, for example, a drive-by-wire system [an electric steering system controlled by a computer] then they need to access the control module to reprogram it. “

In the future, he says, “We very much believe these [tools and capability to access a vehicle’s proprietary systems] will be protected by manufacturers.”

Dykstra sees a lot of changes ahead for his business. Eventually, customers might own not a vehicle, but a share of a vehicle. Cars will talk with infrastructure. They’ll drive themselves into the repair shop when there’s a part that needs to be fixed. But he doesn’t see any of this as the thing that will kill repair shops.

If that happens, he thinks it will be for another reason.

“As long we have fair and equal access to data, information, and training,” Dykstra says, “we will be around.”

Author – Sarah Kesseler

Courtesy of Quartz Media